Exploring Collaboration and Startup Potential

Opening the Door for Joint Ventures and Future Growth Opportunities

One of the biggest challenges in transforming an idea into a functional system or product within a startup lies with the participants—often referred to as the team. Team members must be open about their motivations and future plans, especially as the startup approaches success or expansion. Transparency in these moments is crucial for maintaining trust and alignment.

Investors, in particular, scrutinize the team closely. They assess not only the individual strengths but also the collective resilience of the group—how well the team can navigate discussions on critical issues that could shape the company's future.

Another key challenge is trust. Disclosing either too much or too little about the idea can lead to misunderstandings and potentially erode confidence among stakeholders. Similarly, the effort and commitment from each team member play a decisive role. A startup often lacks the resources to afford expensive services, but it is precisely these investments—both in time and expertise—that can determine its success.

Navigating these complexities requires a deliberate approach. Engage potential collaborators personally, discuss perspectives and motivations openly, and explore the "what ifs"—the potential scenarios, both positive and negative. This preparation not only builds a solid foundation for the company but also reassures investors. They will inevitably ask the hard questions, seeking to understand the solidity of the team and the security of their investment.

It is, of course, a significant advantage if one of the founders has experience in the functional area. Such experience enables the avoidance of many potential difficulties and hazards upfront by identifying the right path early on, saving precious time. This allows the team to focus on progress without needing to document every step in detail, especially when time resources are scarce. Known challenges can be acknowledged and deferred for deeper analysis and discussion at a more appropriate moment.

Specialists and experienced professionals inherently possess the foundational knowledge to anticipate and address issues that will inevitably arise. The better the idea and the smoother its implementation, the sooner external individuals and companies may express interest in profiting from it. This interest could include leveraging parts of the startup's work for entirely different purposes. Similar to a chemical production process, where a stage can be interrupted to extract a side-product for other applications, external parties might seek to repurpose foundational elements of the startup for their own benefit.

At its core, the strength of a startup lies in the unity and resilience of its team. A cohesive and aligned team forms the backbone of the company’s success. Conversely, if this unity is lacking—as numerous examples have shown—the team risks fracturing. Such division can lead to transformations that alienate the original vision, ultimately causing investors to withdraw their support and leaving the company vulnerable to closure.

I experienced this once firsthand when I assisted, free of charge and on a voluntary basis, a company that had the potential to become a giant but ultimately failed due to the aforementioned negative influences.

At the start, there is always the vision and the idea. Without these, nothing can begin. While the idea originates in the mind, it should be put on paper—even if it is summarized in just ten to twenty sentences. This description must be clear, concise, and precise.

Additionally, there might be secondary ideas or potential directions the concept could expand into. For instance, if the idea involves building a platform, it should be specified whether this platform is standalone or if it could serve multiple purposes.

If investors are to be brought on board, a business plan becomes indispensable, as does a well-prepared presentation of the idea. The amount of detail disclosed should strike a balance: revealing enough to inspire confidence but not so much as to expose proprietary aspects prematurely. Since the idea largely resides in the founder’s mind, the presentation can be adjusted and enriched on the fly, depending on the stage and the audience.

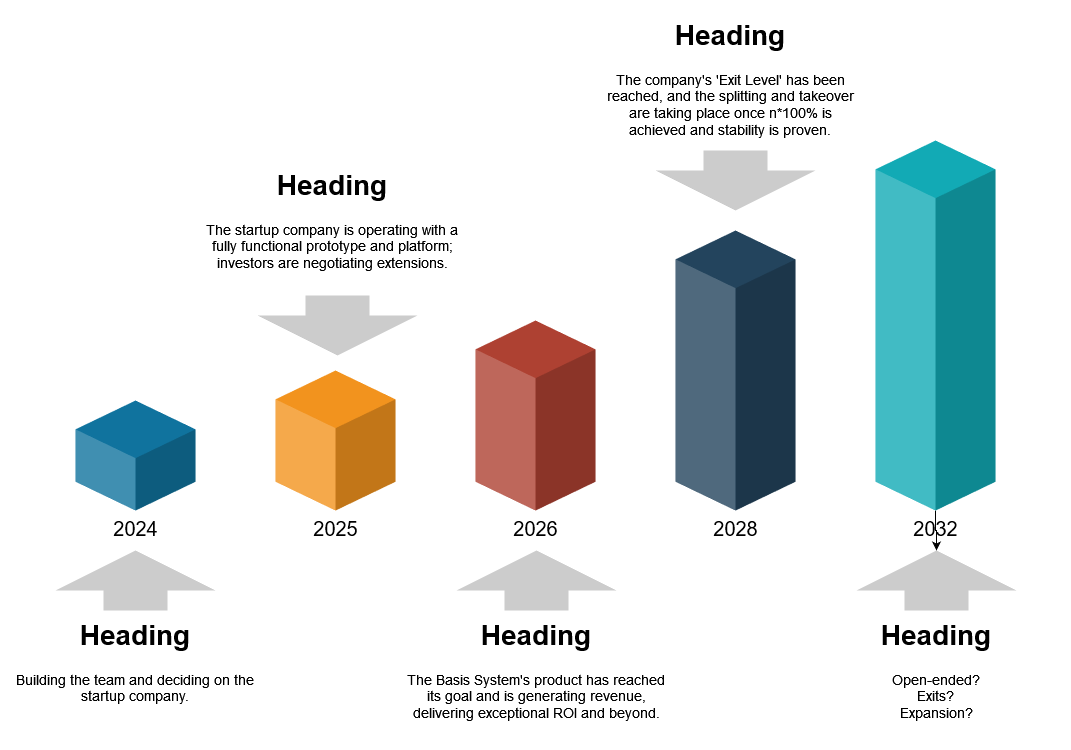

In the planning phase, the main baseline must remain at the forefront. This is the core reason for establishing the startup—the primary goal. This goal should culminate in a tangible version of the product or platform. The key functionalities to be offered should be clearly specified and listed.

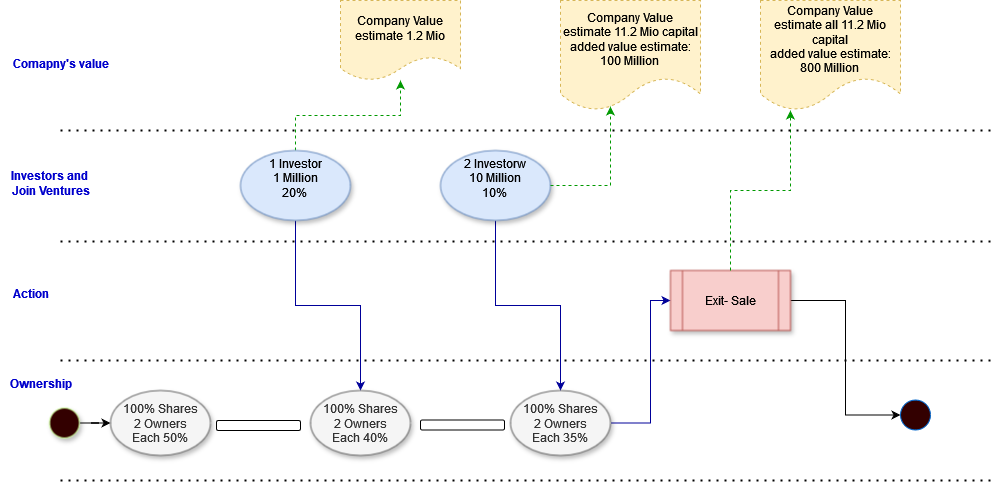

Additionally, the endpoint of this goal must be defined. If the objective is financial—for instance, to increase the company’s valuation and achieve an exit sale—this should be carefully calculated and justified. Why would an individual or company be willing to buy it for a specific sum? What revenue or other benefits would they gain? These questions must be addressed clearly and convincingly.

To explain it simply, as I understand it, the value of a company is primarily based on its capital and inventory—excluding physical assets like software not part of the initial capital. When investors come in, they typically acquire a larger share for a smaller investment, as the risks are higher at the early stages. As more investors join, the share each new investor receives becomes smaller, but their contribution is larger due to reduced risks and the increasing visibility of potential success. It's like taking a slice of a cake that's nearly finished baking.

Eventually, as the project becomes successful, it may not require additional investors because the business can fund itself. For example, by generating large-scale network traffic or through other monetization methods. At that point, there are likely many other options and strategies that I am not fully familiar with yet.

The distinct components of the implementation should be clearly identified—this is, after all, a fundamental step in defining the architecture’s concept. Additionally, ideas for branching off these components into separate side-products should be explored. The stages of development and their versions should also be documented, as this will form a critical part of the business plan.

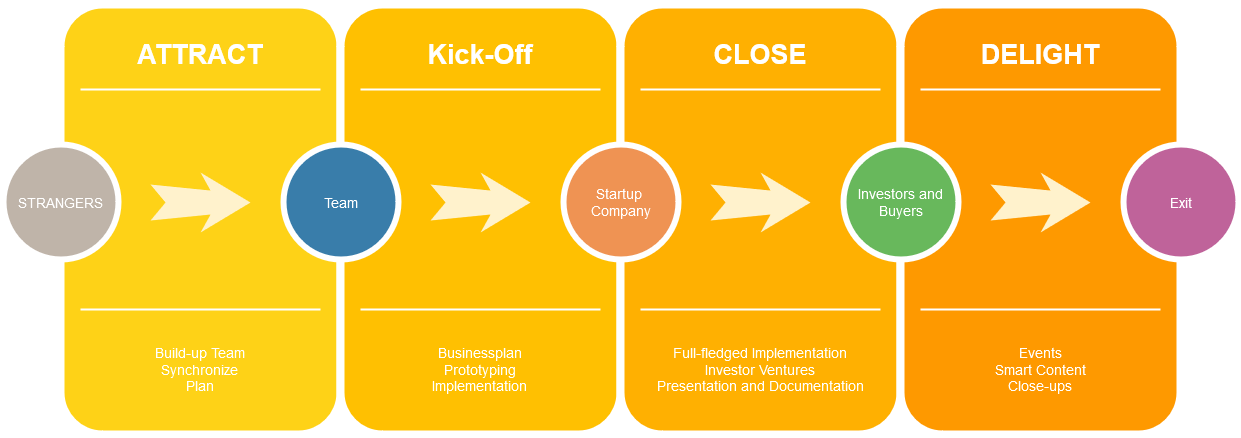

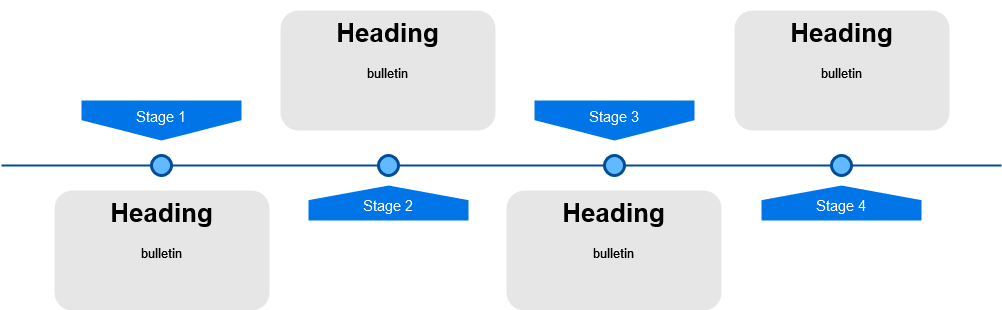

Here’s how the process might look, based on logic, knowledge, and experience:

- Team Formation:

The team members meet to get to know each other, understand their intentions, and align their goals. - Initial Setup:

A minimal business plan is drafted, and a collaborative backend platform is established to facilitate teamwork. - Prototype Creation:

The business plan is refined, and a minimal viable prototype is implemented. - Implementation and Development:

The project progresses through its implementation phase until the primary goal is achieved. - Potential Exits and Iterations:

Along the journey, one or multiple exits—whether final or extended—may take place. Any new ideas that emerge during this process can then follow the same structured approach.

Back to the idea: Sure, caution is necessary, but there's no way around it when transitioning from theory to implementation — it's essential to know with whom you're working. Everyone needs a certain level of security, but it must align with the stage of the process. Many entrepreneurs start alone until they reach a presentable level, at which point they call for others to join. However, bringing people on at that stage tends to be more expensive. The risks are lower, and the outcome is more secure.

Since I’ve also had an idea over the last few years, it can be discussed as part of the intention to promote cutting-edge technologies and contribute to the facilitation of systems with advanced automation.

When considering a startup, not only the vision and the idea are central—though they are the very beginning and the source of inspiration—but practical aspects will emerge immediately. Questions such as how to communicate securely, how to share and process documents, and who will book and manage server resources need answers. If it’s a cloud service, whose credit card will be used?

These considerations are not meant to discourage or dampen the excitement and motivation but to highlight the importance of careful planning right from the first step. And that first step is communication: talking things over, comparing ideas, and ensuring everything aligns.

If you want to be an entrepreneur, join forces with experts and heed their guidance. Otherwise, they might hesitate to let you lead, especially if you’re pushing into uncharted territory with risks that go beyond what is reasonable—risks they may have already encountered and learned from, particularly in professional IT or functional areas.

If you have an idea or are considering joining one, start communicating in a way that ensures all participants understand their roles and positions from the beginning. Without this clarity, the collaboration might fail. Alternatively, if you choose to start alone, you’ll need to take on the risks yourself and outsource critical skills where your expertise falls short. However, this approach can be more expensive and may expose your idea to theft or misuse if it isn’t protected by legal measures.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Startup | A newly established company, typically with a focus on high growth potential and innovation. Startups often operate in developing markets or emerging industries and face high levels of uncertainty. |

| Joint Venture (JV) | A business arrangement in which two or more parties agree to pool their resources and expertise for a specific project or business activity, sharing both the risks and the rewards. |

| Investor | A person or organization that allocates capital to a business venture in exchange for equity, interest, or another form of return on investment. Investors play a critical role in funding startups. |

| Equity | Ownership interest in a company, typically represented by shares or stock. Equity is often given to investors in exchange for funding the company. |

| Exit Strategy | A plan for how an investor or entrepreneur will sell their stake in a company and realize profits. This can include selling the business to another company (acquisition), going public (IPO), or other methods. |

| Prototype | An early model or version of a product built to test and validate the concept. In the startup context, a prototype demonstrates the core functionality of the product or service before full-scale production or development. |

| Minimal Viable Product (MVP) | The simplest version of a product that allows the business to test its concept with users and get feedback with minimal resources. The MVP is essential for startups to determine whether there is a market for their product before making further investments. |

| Business Plan | A formal document outlining the goals of a business, the strategy to achieve those goals, and the financial projections. It is essential for both guiding the startup and securing investments. |

| Value of the Company | The worth of a company, typically based on its assets, revenue, and market position. In the startup world, this also includes intangible assets such as intellectual property and potential for growth. |

| Revenue Generation | The process of earning income through the sale of products, services, or other business activities. In a startup, revenue generation is key to achieving profitability and sustaining operations. |

| Scaling | The process of expanding a business to meet growing demand, typically involving increasing production capacity, expanding into new markets, or hiring more staff. In the context of a startup, scaling is crucial for long-term success and attracting investors. |

| Monetization | The process of turning a business idea or product into a revenue-generating activity. For startups, monetization can take many forms, including direct sales, subscription models, or advertising. |

| Seed Investment | The initial capital used to fund a startup at its early stages. This funding often comes from the founders, angel investors, or early-stage venture capitalists. |

| Exit Sale | The sale of a company to another entity, often representing the culmination of a startup's journey. This may be an exit strategy for the company’s founders or early investors. |

| Due Diligence | The investigation and evaluation of a business opportunity before making an investment. It involves assessing the startup’s financial health, market potential, and risks. |

| Stakeholders | Individuals or groups that have an interest in the success or failure of a business, such as founders, investors, employees, and customers. Stakeholders can impact the direction and operation of the startup. |

| Exit Route | The pathway a startup follows to eventually exit the market, which could include acquisition by a larger company, an initial public offering (IPO), or other methods of selling the business. |

| Transparency | Open communication and sharing of relevant information within a business. Transparency is crucial for building trust among the team, investors, and stakeholders, and for avoiding misunderstandings. |

| Risk Mitigation | The strategies used to minimize the potential risks in a business venture. For startups, this involves careful planning, gradual scaling, and securing adequate investment. |

| Burn Rate | The rate at which a startup is spending its capital before generating any revenue. A high burn rate is common in the early stages but can lead to problems if not managed properly. |

| Business Model | The plan implemented by a company for how it will generate revenue and make a profit. Common models for startups include subscription, freemium, and advertising-based models. |

| Stakeholder Alignment | Ensuring that all key participants—such as founders, employees, and investors—are on the same page regarding the company’s goals, strategies, and operational methods. |

| Scaling Up | The process of growing a startup’s operations to handle a larger customer base or market share. Scaling typically involves investing in infrastructure, hiring new employees, and expanding marketing efforts. |